Insights

Hope for a new gold standard?

Share this article

April 8, 2024 | By Mesirow Currency Management

Bretton Woods: An attempt to avoid post-WWI economic mistakes1

Following World War II, gold played a pivotal role in the post-war international monetary system. Representatives from 44 Allied countries met at the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference held at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire in July 1944.

The Allies created the Bretton Woods agreement in which the United States agreed to convert US dollars to gold at $35 per ounce. Nations maintained fixed exchange rates with the dollar instead of developing conversion rates between their currencies and gold. Despite gold’s terrible economic record in the inter-war years, the Allies placed the world on a de facto gold standard.

Mount Washington Hotel Resort - Site of the Bretton Woods Agreement

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Because gold, once again, was a crucial component of the international monetary system, it was reasonable to position the world’s economic superpower – the United States with its 75 percent share of the world’s monetary gold - as the central agent of the system. In stark contrast to the uncoordinated, every-country-for-itself environment during the 1930s, the US fostered an international sense of purpose to rebuild devasted nations.

By the end of the 1950s, that revitalization effort had progressed astonishingly well, so well that nations which barely survived the first few post-war years were positioned in the 1960s to challenge the US as formidable business competitors.

As business in Europe and Asia increased, Americans bought those nations’ exports and invested in foreign businesses. At the same time, the United States funded numerous domestic social programs; positioned troops in Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom and elsewhere; battled Russia and its East European allies in a cold war and fought two hot wars in Asia. These imports, business investments, social programs, and foreign policy actions were inadequately funded, resulting in large outflows that caused the US inflation rate to rise and the gold stock to decline.

US gold holdings, $22 billion in 1958, decreased by $3 billion by the end of 1960. At the same time, foreigners owned $20 billion worth of Treasuries and deposits in US banks, exceeding the US’s capability to exchange gold for these obligations. Meanwhile, inflation became entrenched in the economy, with prices rising even during the 1970 recession by 5.7 percent.

The Viet Nam war intensified the pressures on the dollar and gold. Increased defense spending, without a commensurate rise in taxes to fund the conflict, put foreign holders of US dollars in a quandary. Selling dollars would cause a decline in the dollar exchange rate, reducing the value of their vast holdings of the US currency. But holding US dollars in a high-inflation environment was unsound. Foreigners found a solution: they exchanged their dollars for gold at the US Treasury, further depleting levels of the precious metal.

Despite steps to make holding the dollar more attractive compared to holding gold and to keep gold onshore, nothing worked. Gold levels declined from $22 billion in 1958 to $10 billion in 1971 while foreign liabilities rose every year during that period to over $60 billion.

Speculators and de Gaulle see an opportunity

The fiscal position of the US didn't go unnoticed by speculators, and they bought gold in anticipation of a devaluation of the US dollar. The United States and its European allies, worried that speculators could cause the gold price to rise above the official rate of $35 per ounce, formed a gold pool in 1961 to sell gold whenever the price rose above $35.

At first, because of increased mining of the precious metal, the pool was able to buy gold at $35 per ounce, but as the US fiscal position deteriorated, the pool sold gold to steady the official price. Pool participants increased gold sales to such a level that speculators recognized that the participants’ currencies would likely devalue, causing the price of gold to rise substantially. The pool could not keep up with the speculators; in 1967 the pool capitulated, allowing central banks to continue to purchase gold at $35, but giving up on controlling the London market price of gold.

Politics weighed on gold matters too. French president De Gaulle, seething over decades-old slights to him and his country regarding France’s exclusion from wartime decision making, tried to make the economic situation as unpleasant as possible for the United States and its currency. He clamored for the gold price to be set at $70, but the world ignored his plea. No one wanted to double the world’s monetary base and experience the resulting inflation.

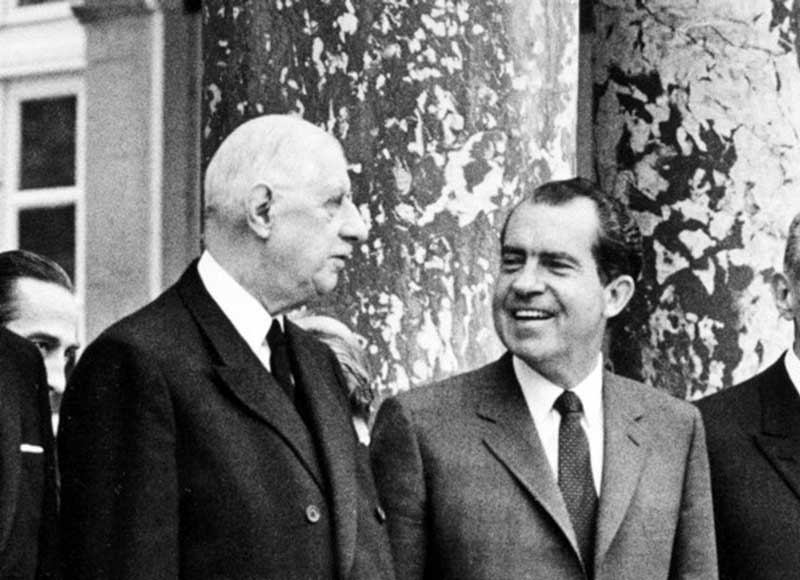

President Nixon and De Gaulle in Paris, 1969

Source: Richard Nixon Foundation

De Gaulle tried to frustrate the US on other fronts too, such as withdrawing French forces from the integrated military command opposing the Soviets. He was compelled, however, to turn attention from thwarting the US to dealing with labor riots that crippled the French economy.

The turmoil caused a run on the franc, and money flowed to the Swiss franc and German deutsche mark. The battle over gold, the violent labor problems, and the fall in the franc were too much; De Gaulle was forced to resign in 1969.

High unemployment or wage and price controls

De Gaulle’s resignation was just one incident in a period filled with momentous events and challenges. Top of the economic challenges list was inflation. The new US President, Richard Nixon, was faced with the economic choices the British confronted in 1931: Nixon could either dramatically increase interest rates and taxes to stabilize the price of gold and the position of the US dollar, or he could control wages and prices in what became known as incomes policy. The first option would likely result in unacceptable social costs of high unemployment and low business activity. Incomes policy seemed the much more palatable process.

The president had to convince labor to hold down wages while encouraging industry to maintain prices. Assuring manufacturers that wages wouldn’t increase would result in steady prices, pleasing labor which worried about the deterioration in worker’s purchasing power. If those two aims could be achieved, it would avoid a crushing recession and the political cost of losing the presidency in the next election.

Congress granted the President power to enact price controls in 1970. The President turned to Treasury Secretary John Connally to implement the plan. The first action was to end gold sales. After two hundred years, except during the Civil War, the US would not exchange gold for dollars. Connally and Nixon expected the dollar to decline, making it easier for foreign consumers and businesses to purchase US products. That would help American businesses and labor who would expect a rise in employment. That business increase would be inflationary, so the President and Treasury Secretary designed a series of wage and price controls to manage inflation.

The President packaged the closing of the gold window, price controls, an import duty of 10 percent on many products, tax cuts for business, and reduced government spending into his New Economic Policy. It was a stunning political success: the US bond and stock markets soared after the ‘Nixon shock’ was announced.

The Nixon Shock

Source: New York Times

Overseas the reaction was uncertainty. Foreign exchange trading halted while officials tried to plan a response. The Japanese continued to trade however, with Japan’s central bank buying dollars to stabilize the yen’s dollar exchange rate, but it soon gave up. The Japanese central bank’s failure foretold the outcome for other currencies, and as other trading resumed, central bankers watched their currencies appreciate and the dollar decline. New sets of exchange rates were negotiated and agreed, but those exchange rates were temporary: inflation was too great, and beginning in 1973, currencies were allowed to freely fluctuate. That same year, wage and price controls were abandoned.

A decade of frustration

The 1970s was a decade of economic frustration. The world grappled with high inflation, stagnating business, oil embargoes and skyrocketing energy prices. Central banks sold gold believing that no commodity made sense as the basis for monetary policy.

And so, after a few years of adequately, or even admirably, supporting economic wealth and welfare, gold appeared done in by the impossible task of a single nation managing an international monetary program that conflicted with domestic social, political and economic aims and problems. But gold wasn’t done.

When Paul Volker, the Federal Reserve chairman, raised interest rates in 1980, he took a page out of the British economic playbook. The interest rate hike successfully crushed inflation, but gold had one last hurrah, soaring to $850 per ounce in January 1980. That was the market peak for decades.

Gold, in early April 2024, is about $2350 per ounce, but its price is no longer coupled to global monetary policy. Instead, the US dollar runs the economic show.

What would the Lydians, creators of the first gold coins, think?

The Lydians might look at these gold events with disbelief. What went so wrong? We might respond: In theory a gold standard is appealing, but maintaining gold levels to support currencies could result – has resulted - in painful economic consequences for millions of people.

And who will be the gold keeper? The twentieth century every-nation-for-itself-gold-standard strategy failed miserably. And the United States found it impossible to manage an international gold standard while addressing domestic needs.

Russia and China might be glad to oversee gold levels as part of their BRICS currency responsibilities, but the United States and its allies would balk at gold flowing from their central banks to countries who are overt antagonists at best and covert enemies at worst.

Perhaps basing an international monetary standard on a mineral, one that is finite in volume and which unmined quantities are often located in places that are inhospitable to western nations, might not be the best idea.

If well designed and executed fiscal and monetary policies are the goals, is it necessary to be yoked to a metal to achieve those objectives? Having developed the policies, could central banks and treasuries simply follow strategies that are designed to keep debt and inflation low? At the same time, could those central banks also provide adequate liquidity to meet business and investment needs with the occasional exceptional expansion of the money supply to address economic or social disasters like the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic?

The Lydians would shrug: “That’s what we did.”

1. Peter Bernstein’s The Power of Gold: The History of an Obsession is the main source for this article.

Explore more currency insights

Gold gets a good start

Gold has been money or the basis for monetary systems for centuries. How did gold become the ultimate backing for nations’ currencies in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries?

The gold standard

The Great War (1914 – 1918) shattered the world. In the conflict’s aftermath, people desperately wanted to recreate pre-war tranquility. How did gold affect the world’s desire for peace and harmony?

Spark

Our quarterly email featuring insights on markets, sectors and investing in what matters