Insights

Gold gets a good start

Share this article

February 27, 2024 | By Mesirow Currency Management

Is gold the cause or consequence of peace and prosperity?

One link that connects generations and joins ancient societies to modern ones is money. People, no matter the era, need to trade, save and guard against uncertainty.

Gold was a popular form of money for thousands of years until it fell out of favor in the 1970s. Fifty years later, gold is attempting a comeback. In July 2023, Russia caused a sensation when it announced plans for a gold-back currency sponsored by the BRICS nations – at that time, Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. In October 2023, Zimbabwe issued a gold digital token that can be used as legal tender.

Should the world reconsider gold as the basis for an international monetary system? In a three-article series, we examine gold’s history, focusing on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries when gold was in a prominent monetary role.

This first article discusses gold’s start as money, its struggles with silver in a bimetallic financial system and how it became the standard for many nations’ currencies. Countries took themselves off the gold standard to finance World War I, and our second article describes the efforts to reestablish the gold standard after combat ended. Lastly, our third article examines gold’s role in international finance during the decades that followed World War II.

Gold money1

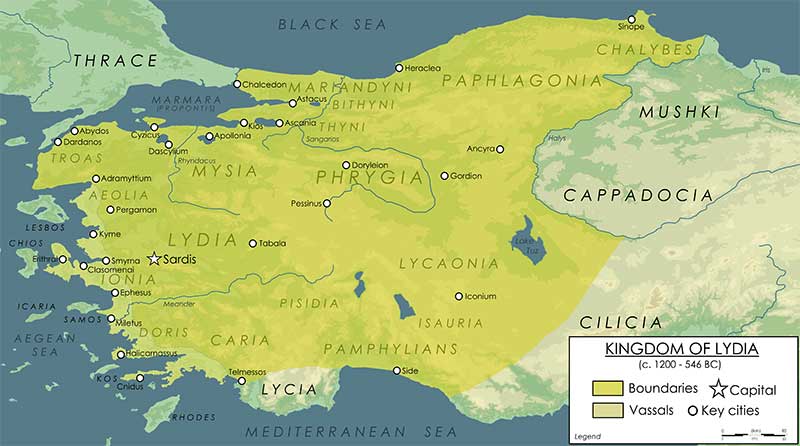

We can thank the ancient Lydians for the creation of gold money about 2600 years ago. The Lydians, in turn, can thank their property instincts for enabling their historic contribution. The Lydians knew the first rule of real estate: ‘location, location, location’. They situated themselves alongside a major east-west trading route in modern-day western Turkey and next to a river with an abundant source of gold.

Kingdom of Lydia

Source: Wikimedia Commons. https://w.wiki/9E27

The Pactolus river, near the Aegean coast in present-day Turkey, was (said to have been the site) where King Midas rid himself of his ‘golden touch’ and where the Lydians sourced their precious metals. They mined gold and a metal called electrum, a combination of gold and silver. The Lydians mastered production of easy-to-carry gold and silver coins of consistent purity and weight, sparking a surge in commerce and business.

Source: Classical Numismatic Group, Inc.

Remarkably, this bimetallic system lasted from the ancient Lydians through to the “Nixon shock” in 1971 that formally ended monetary standards based on gold or other precious metals.

Gold triumphs over silver

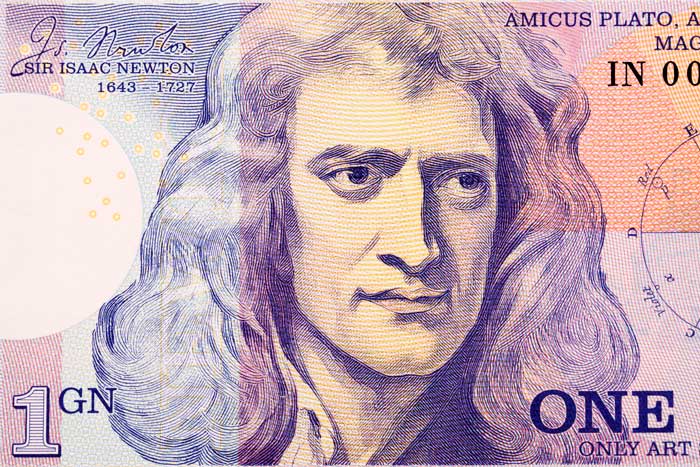

The eighteenth century saw an unusual sight: Isaac Newton – a candidate for the greatest-of-all-time scientist award – became Master of the Mint. The Kingdom of England was on a bimetallic standard – silver and gold were accepted for taxes, as legal tender and as payment for goods and services.

Source: Getty Images

In 1717, Newton set the price of a troy ounce of gold and troy ounce of silver. He thought that silver’s price would be fixed and that gold’s price would fluctuate. Evidently, being an economist is more difficult than being a scientist, for it was the other way around: the price of an ounce of gold would remain 3 pounds 17 shillings until World War I, almost 200 years.

The important fact, though, is that gold became the sole standard of money.

Gold triumphed over silver in America too. Advocates for the two metals fought fiercely for dominance, and the fight took on the aspects of a class struggle: farmers and small businesses who promoted silver against east coast financiers and industrialists who favored gold, a Little Man vs Established Powers conflict.

The gold standard triumphant

Source: Wikipedia. The gold standard triumphant: a caricature from Puck magazine, 1900 cartoon by Louis Dalrymple published in "Puck" magazine, via Library of Congress website at https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2010646248/

Following the Civil War, problems with deflation and the convertibility of paper to gold or silver (convertibility had been discontinued during and after the war, a standard procedure for financing an armed conflict) led to passage of the Coinage Act of 1873. This legislation, through no deception or intention, failed to include silver as part of the money stock.

As a result, the United States unintentionally moved to a monometallic standard, that of gold alone.

Gold as money sees the beginning of its end

Coins worked well in commerce, but gradually trade and finance began to change from a metallic-based system to paper because trading became more complicated. Instead of a simple coins-for-merchandise exchange, buyers sometimes needed to finance a transaction. This led to bills of exchange and promissory notes and an unprecedented situation: government funds and minted coins coexisted with private paper money.

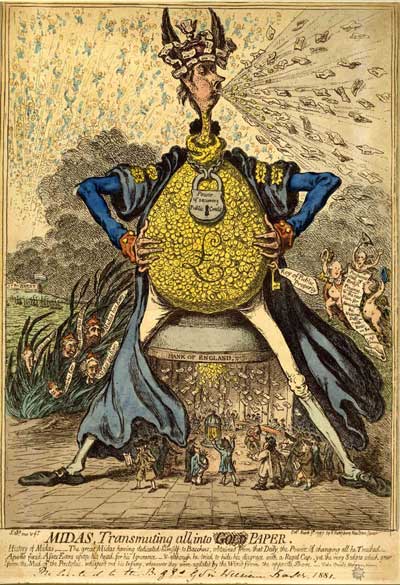

Trust and comfort with paper money got a boost in 1797 when an event occurred that set the scene for money as we know it today: without a gold backing. Rumors that a French fleet landed troops in Wales set off a banking panic, and people lined up at the Bank of England, the nation’s central bank, to withdraw gold.

The run lowered the stock of gold to dangerous levels; in desperation, bankers and merchants issued a statement saying they would accept banknotes (paper money) until the crisis eased and gold could be safely withdrawn (which didn’t happen until 1821). Everyone took a deep breath, carrying on without worry, knowing that (eventually) the gold standard would be reestablished.

Midas transmuting gold to paper

Source: ‘Midas Transmuting all into Gold Paper,’ James Gillray, 1797. Bank of England Museum: 0276

Nineteenth century reverence for gold

It wasn’t just a genius’s mistake or unintentional legislation that turned the world into a gold-based financial system. Gold’s luster dawned from early history. Its relationship to power and prestige combined with its longtime role as a medium of exchange led to gold becoming the basis for the gold standard.

In the 1800s, when nations defined their currencies in terms of gold, those conversion rates were immutable. And everyone knew the gold-to-currency exchange rate was unchangeable; one could depend on the fact that, no matter what, one would receive the same amount of gold for a unit of currency today, tomorrow, and forever after. It was of enormous importance to anchor a nation’s currency to gold, a demonstration of credibility among a group of big countries that insisted on adherence to a gold standard.

That adherence became more firmly reinforced by a ‘this-is-as-good-as-it-gets’ period of international peace and industrialization that led to robust economic growth from (about) the end of the US Civil War (1865) until the beginning of World War I (1914). This 50-year period during, first, the reign of Queen Victoria and then her son, King Edward VII, cemented the allegiance to a gold standard.

Many people attributed this prosperity and peaceful period to the gold standard, although some historians argue that the gold standard was more a consequence than a cause of the era’s tranquility and prosperity.

Queen Victoria's golden reign: 1865 – 1901

Source: Getty Images

Some contemporaneous observers had the same opinion as those future historians about the role of gold in those good times. The British prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli, described the nature of the gold standard when he spoke to Glasgow merchants in 1873. “It is the greatest delusion in the world to attribute the commercial preponderance and prosperity of England to our having a gold standard,” Disraeli said. “Our gold standard is not the cause, but the consequence of our commercial prosperity.”

It didn’t matter what the prime minister said. Gold was golden, and hardly anyone (an exception: German economist and philosopher Karl Marx) disagreed.

1. Peter Bernstein’s The Power of Gold: The History of an Obsession is the main source for this article.

Up next

Our second article on gold as money. We talk about the aftermath of World War I: How did gold affect the world's desire for peace and harmony?

Explore

Cryptocurrencies and Tokenization

Distributed ledger technology fosters digitization of just about everything.

Futures overlays for investors

Hedge Share Class Investors Grapple with Shorter (T+1) Security Settlement Cycle.

Spark

Our quarterly email featuring insights on markets, sectors and investing in what matters